by Jordy Yager

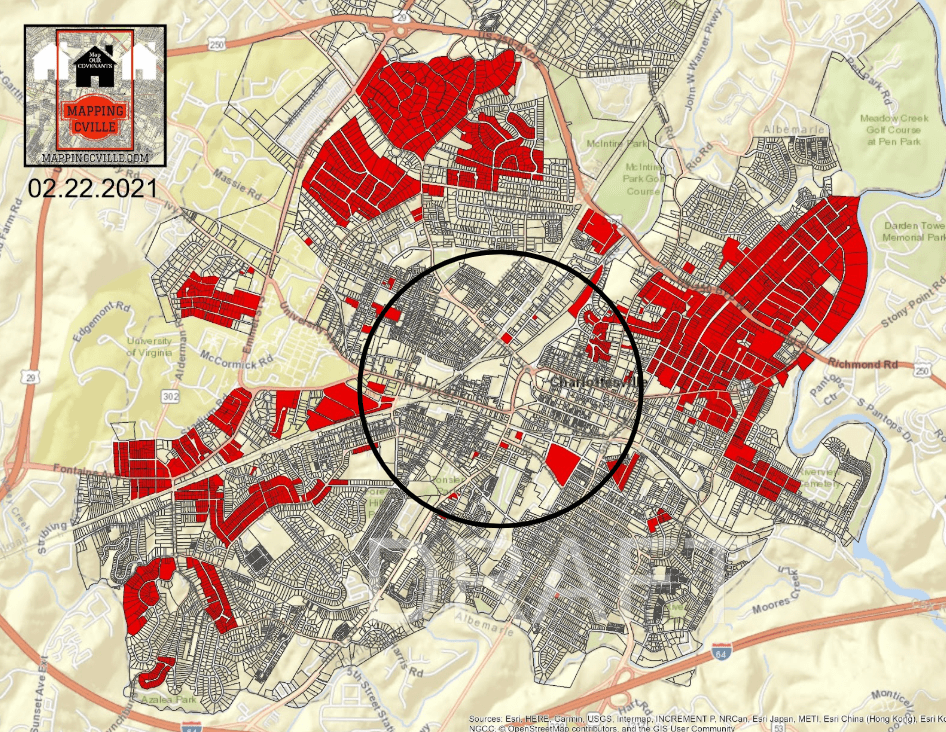

I first started this website to chronicle the mapping of racial covenants in Charlottesville and Albemarle County. Over the past several years hundreds of you have helped document more than 2,500 deeds with this racist language in them, about 58% of which we’ve successfully mapped so far. We continue to make our way through Albemarle County’s much vaster records (help us here), but the more we dig into these racially restrictive records, the more something else has emerged: the origins of historically Black neighborhoods and communities.

In 2022 I was hired to work full-time as the Director of Digital Humanities at the Jefferson School African American Heritage Center, where I’d been working with Executive Director Andrea Douglas on a project-by-project basis since 2016. In this new role we received funding from the Institute of Museum and Library Services to launch the Black Land Repository, a database and full accounting of every Black-owned property in Charlottesville from its incorporation in 1888 until its records ceased to be segregated in 1950.

Much of this research, which continues today, has resulted in the newest installation in the JSAAHC’s Pride Overcomes Prejudice exhibition. Installed in September, 2024 on the Jefferson School’s first floor the exhibition is entitled Toward a Lineage of Self and uses a digital map to tell 125 interconnected stories of Charlottesville’s founding.

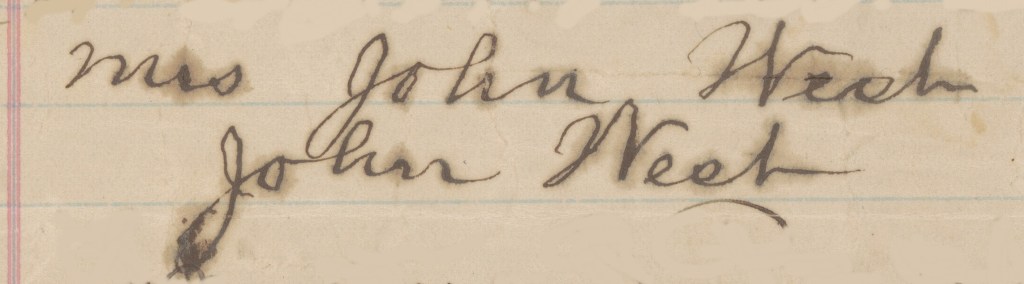

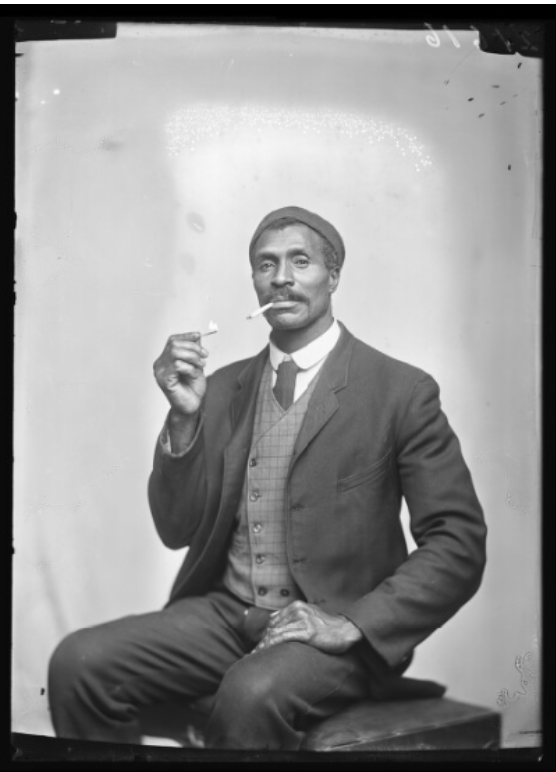

Portions of this history have been known, but often in isolation. For instance, who was the first Black property owner in Vinegar Hill? If you’re a longtime reader of this site, you know we found records showing that in 1870 John West bought land there for $100. We also know that the land that became Vinegar Hill was part of a former plantation. But what we didn’t know was how Vinegar Hill became a neighborhood? John West bought land there, and then what? And what else did John West buy?

We knew we needed to cast a wide net, so I digitized thousands of pages of records at the City and County Courthouses, as well as at the University of Virginia’s Law Library. And working with my intern Joshua St. Hill, we created the first database of every property John West and his wife Darrie Barnett West ever owned. And then we began to map, because having the records is one thing, but seeing the relationships and networks is something else entirely.

In total the West’s owned more than 400 properties, often selling Black families their first home. They were also landlords to dozens of people, like Bill Hurley, who rented from the West’s in the heart of 10th and Page. Hurley worked as a porter at the Gleason Hotel on West Main Street, and had family in Vinegar Hill, down the street from the West’s own home.

The West’s were not alone. The research I’ve been doing reveals that in 1867 Black families were buying land in what became Fifeville. In 1868 Kellytown was beginning to form. In 1869, Gospel Hill. After Emancipation, the city was rapidly growing, and Black residents were building it.

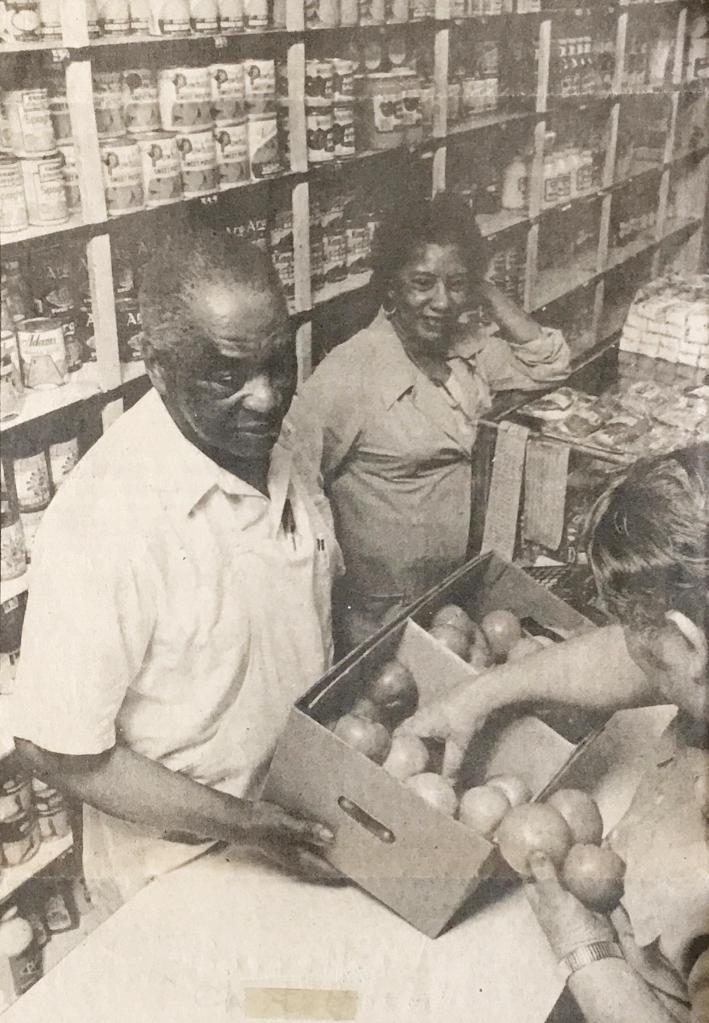

Over on Garrett Street, in 1875, Walker Allen purchased land that would be home to his son and grandson, and their families, who lived there and operated a butchery, a grocery, and general store there for nearly 100 years. Before Urban Renewal forced them to move to Rose Hill Drive in the 1970s, Walker Allen’s grandson Kenneth Allen and his wife Dorothy ran Allen’s Store for decades as the neighborhood grocery store on Garrett Street.

Going back to the 1870s, when Benjamin E. Tonsler and Robert Kelser were young 20-year olds, I have to believe they would have grown up hearing stories about this active Black community building. When Tonsler and Kelser graduated from the Hampton Normal and Agricultural Institute, in 1874 and 1876 respectively, they bought property in Fifeville and Starr Hill and began teaching at what became the Jefferson School. Kelser became Vice Principal and Tonsler its Principal, a position he held for over 30 years. In fact, in 1894 Kelser and Tonsler helped organize the construction of the two-story brick Jefferson Graded School on the corner of Commerce St. and 4th St. NW.

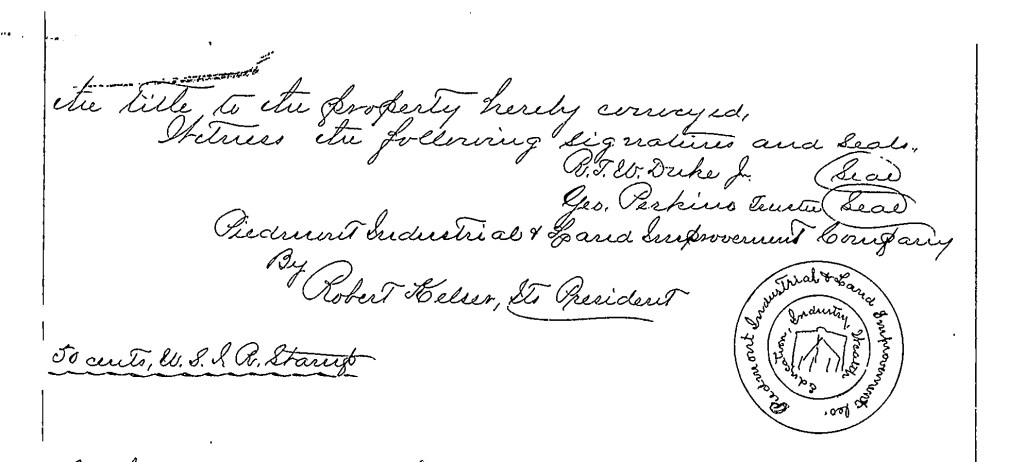

Five years earlier, in 1889, Kelser and Tonsler joined seven other Black men to build something else entirely—the Piedmont Industrial and Land Improvement Company, the first Black real estate company in Central Virginia. We knew that much, but nobody had ever looked at the extent of the PILIC’s properties. So we tracked them all back, and mapped them. We also learned that the PILIC operated for over 25 years, and had more than 50 shareholders, which we mapped as well. With this fuller picture, we began to see what Black neighborhood development looked like and the widespread collective support that made it possible.

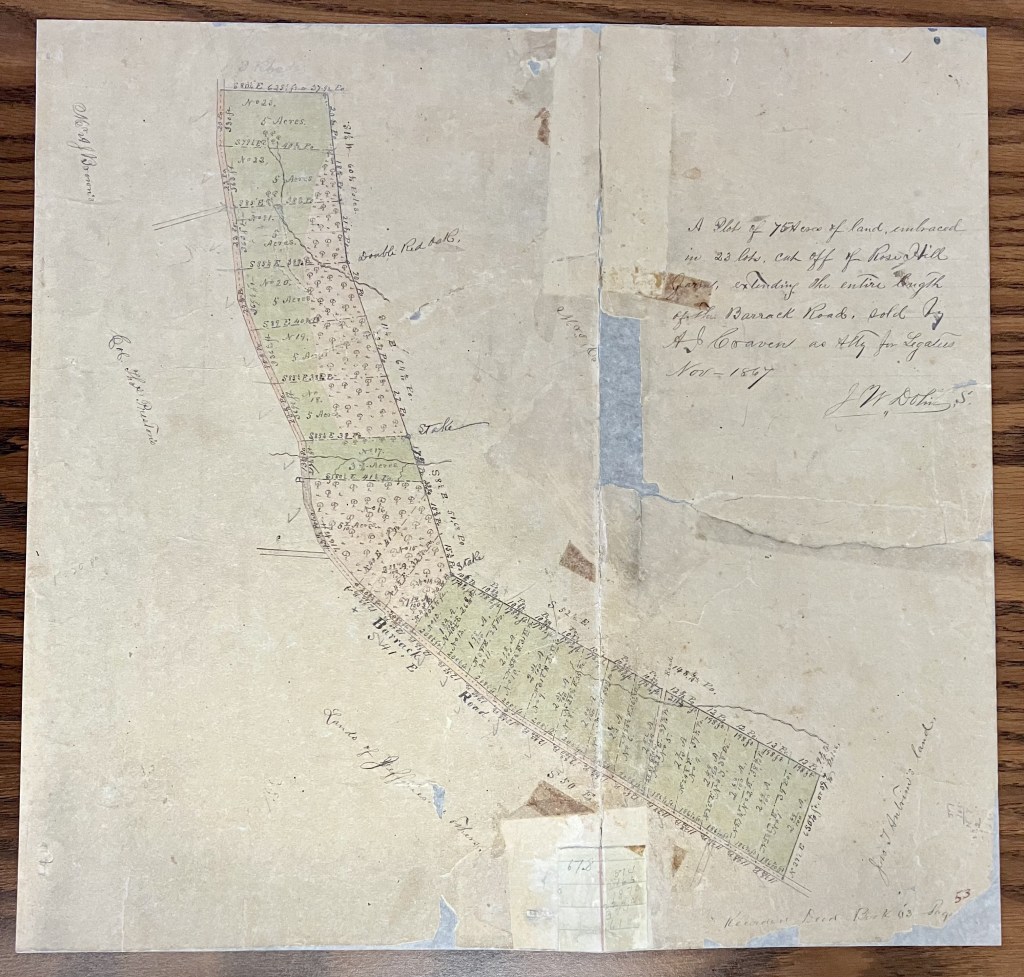

In 1890 the PILIC purchased 15 lots on the west side of Charlottesville, near what would become Booker T. Washington Park (its namesake was a classmate of Tonsler and Kelser’s at Hampton). The area was beginning to be known as Kellytown, named after Alexander Kelly, a plasterer and the area’s first recorded Black property owner.

In 1995, Kelly’s great grandson, Joseph Kelly, Jr. gave an oral history.

“You could write a letter from Australia and put ‘Kellytown, Charlottesville, Virginia—everybody knew everybody, the whole town was so small.”

— Joseph Kelly, Jr.

Kelly said chestnut trees lined the dirt road (Barracks Road) running through Kellytown. He recalled a nearby apple orchard, cherry trees, and a slaughterhouse. Neighbors had milk cows, he said, and gardens with cantaloupes and watermelons. In the summer he and his friends would dam Schenk’s Branch and swim.

After graduating from Jefferson, Kelly landscaped the UVA hospital grounds for 10-cents an hour.

“When I first went to school, the farthest you could go was eighth grade. To get into college, you had to go to prep school because you didn’t have enough credit—we had different books.”

— Joseph Kelly, Jr.

Life was a mixture of beauty and joy, alongside hardship and discrimination.

Kelly’s father worked on East Main Street at Pence and Sterling pharmacy. His aunt, Ella Baylor, taught for 41 years at Jefferson School. In 1983 Baylor recorded her own oral history.

“In the Black neighborhood…there was nothing but mud and only room for one wagon on the streets. The White neighborhoods were lovely.”

— Ella Baylor

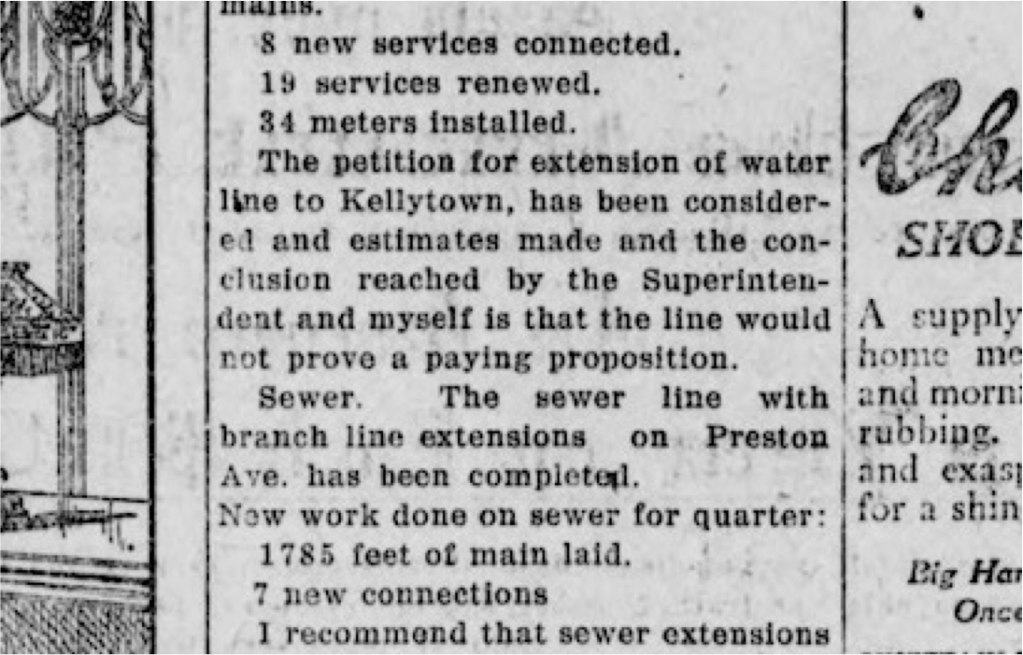

Through the research of Steve Thompson I learned that in 1917, the same year Joseph Kelly, Jr. was born, the city denied Kellytown’s petition for municipal water and sewer lines. We know, through the JSAAHC’s oral history archive, that other Black neighborhoods were denied this basic infrastructure access. So I dug through City Council minutes and, working with UVA students, created a database of every infrastructure request from 1904-1939. I’m currently mapping these data, analyzing them for patterns of systemic disinvestment and racialized abandonment.

The history of systemic and structural racism in Charlottesville is deep and wide-ranging, from the advent of racial covenants in 1893 and the city’s segregated housing ordinance of 1912, to the razing of seven Black neighborhoods between 1918-1973 and the discriminatory lending practices of banks and financial institutions. Toward a Lineage of Self chronicles all this and more.

This work sits at the core of the JSAAHC’s Center for Local Knowledge (CLK), where we combine oral histories with original research to support and meet community needs. Our goal is to foster and contribute to honest reckoning of how our history has shaped our present because while it is important to understand Charlottesville’s history through the lens of land, the JSAAHC poses another vital question: What does this historical understanding help us do today?

And that is where we are calling on you, our community. As a digital exhibition Toward a Lineage of Self was created to continuously expand. It is set up to contain audio and video interviews, and to tell contextualized narratives using archival images, records and maps, so the rich and personal history of Black space may always have a fully articulated home. It was also created to be a tool to both better the lives of community members today, and to help create a new future. Every time you visit the JSAAHC, the exhibit will have changed, becoming expansive, more powerful, and even more interconnected.

Jordy, This work is a GIFT to the current and future students, community members and leaders of Charlottesville and surrounding counties.

Thank you so much for all you and the JSAAHC have done to make it historically inclusive and accurate, engaging, and thought provoking as it continues to evolve and inform.

I continue to share it as the model for other locales engaging in this work.

Much appreciated, Annie

Annie Evans Director of Education & Outreach New American History University of Richmond Anne.Evans@richmond.edu https://www.newamericanhistory.org/ @MapM8ker

“A map is the greatest of all epic poems. Its lines and colors show the realization of great dreams.” ~ Gilbert H. Grosvenor, Editor of National Geographic (1903- 1954)

LikeLike