We’re making great progress! After launching the public portion of the Mapping Cville project less than two months ago, we’ve completed more than 1,200 loggings of racially restricted properties in Charlottesville, retiring more than 200 deeds.

So let’s get to mapping!

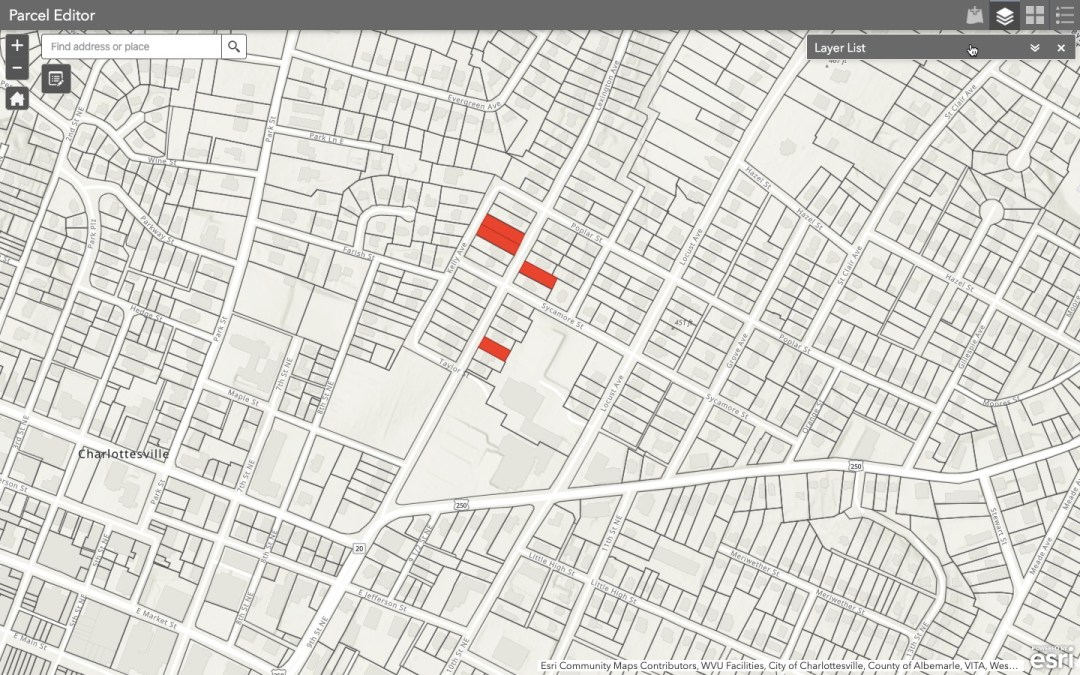

The very first properties we’re able to map are 4 on Lexington Avenue:

Which is in the Martha Jefferson neighborhood.

A note on process: We’re logging and mapping these deeds as they appear in a property record’s history, which may not be at the beginning of when that property was created, but rather, as is the case here, the deed may come a little ways into the property’s lifespan. I’ve grouped these 4 properties together into one blog post simply because they are ready to be mapped and are in the same general vicinity of one another.

Two of these four properties were sold in 1906, one in 1909, and one in 1928. It’s a little bit of a stretch to imagine what it was like back then, but I like to squint my eyes and try.

Not all of these properties had houses on them when they were sold, but we know some did. In fact, we know that the Locust Grove Investment Company had at least 11 houses built on speculation in the 1890s in an attempt to entice people to buy land and build more houses.

Some history — For thousands of years, this area was traveled through and lived in by Monacan Indians. In the early 18th Century, white Anglo-Americans pushed into the area, and in 1735 Nicholas Meriwether received a land grant of 1,020 acres that included this land. Meriwether was the largest landholder in Albemarle County and one of the largest in all of Virginia, amassing more than 30,000 acres of land, and enslaving many people over the course of his life. This particular 1,020-acre tract stretched west of the Rivanna River and became Meriwether’s plantation known as “The Farm.” (Interesting fact: In 1865, after the Confederacy was defeated in the Civil War, U.S. Gen. George A. Custer is said to have briefly occupied the main house on “The Farm” over a period that brought liberation and freedom to black people who had been enslaved.)

For more history on the neighborhood, see here, here, here, and here.

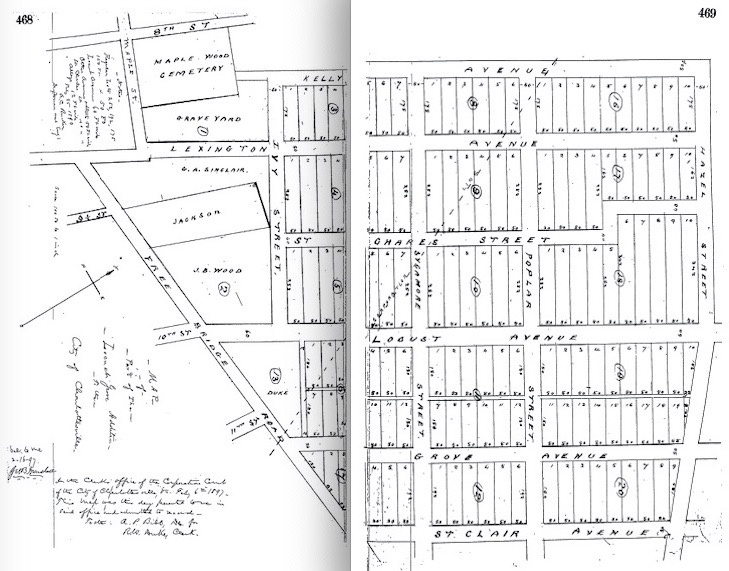

By the early 1890s, Meriwether’s plantation had changed hands several times, and a group of local white men formed the Locust Grove Investment Company, which then acquired and subdivided a portion of it, as you can see here in this plat.

And here’s what these 4 properties look like when overlaid with this initial 1897 platting:

Next to this 1897 Locust Grove plat was the following deed:

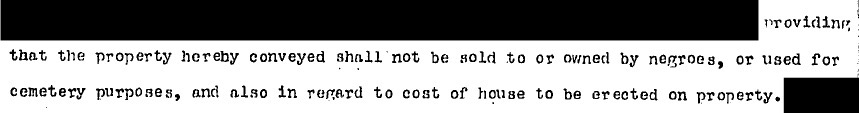

About halfway down the page, you’ll see the following clause:

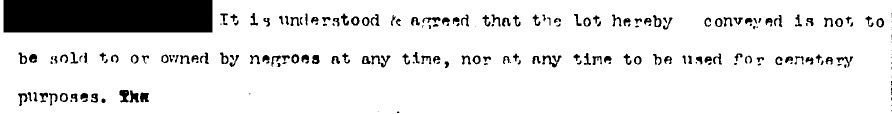

About halfway down the page, you’ll see the following clause:

“It is also agreed that this land is not at any time to be sold to or owned by negroes.”

Charlottesville incorporated as a city in 1888, and it included this large portion of land, near Court Square and what would later become the downtown area. It was primed for residential development. Big lots, open space, good drainage.

By 1900, Charlottesville had a population of 6,447 people:

White residents: 3,834 (59.5%)

Black residents: 2,613 (40.5%)

Yet, George R. B. Michie and other founding investors in the Locust Grove Investment Company decided to restrict the sale of all 140 of these Locust Grove properties to only white residents. It’s the first instance I’ve found of a racist covenant ever being used in Charlottesville.

One thing we’re documenting with this project is how this racist language evolved.

In 1906, the deed says…

“This conveyance is made subject to all restrictions … providing that the property hereby conveyed shall not be sold to or owned by negroes, or used for cemetery purposes, and also in regard to cost of house to be erected on property.”

In 1909, the deed says…

“It is understood and agreed that the lot hereby conveyed is not to be sold to or owned by negroes at any time, nor at any time to be used for cemetery purposes.”

In 1928, the deed says…

“This conveyance is subject to restrictions of record as to Caucasian ownership and use for cemetery purposes.”

What’s also interesting is that two of these properties were bought with cash, for $2,500, in 1906. When adjusted for inflation today, that’s $71,381.67. But, of course, that’s not the most accurate measure of how much it’s worth. For that we look to the relative income calculation, which is somewhere between $346,797-$613,650 and find that this is more in line with the assessed value of these homes today, which are between $583,900-$664,000.

Not all of these properties were paid for with cash though. The 1928 property was bought using a mortgage from The Peoples National Bank.

In 1927, according to the City Directory, the president of The Peoples National Bank was none other than George R. B. Michie, a founding member of the Locust Grove Investment Company and the previous owner and seller of the two 1906 properties outlined here. And you might have noticed here also that the bank’s cashier was a man named H. A. Dinwiddie—he was also one of the sellers of the 1909 property mapped here.

A final note: This is by no means an exhaustive blog post; it’s meant to be the first of many, and one that will be continually added to as we map more properties in this area. As the map begins to be filled in, so too will our shared history. That said, I’ve already had several people express interest in writing a personal public history of their own properties, which is to say that if you have any desire whatsoever to dig deeper into any of this history—personal or otherwise—I would love that.

Also, we’re in the final stages of getting all this information, and more, loaded onto a live and interactive map for people to use, so I’ll be sure to keep you posted on that.

And we also have a paper map that we’re filling in at the Jefferson School African American Heritage Center, where our final digital map will live, so come by and check it out if you can.

And more mapped properties are COMING SOON!

2 thoughts on “1. Lexington Ave”